The ubiquitous Thar-Parkar desert, the Aravalli hill range and water are three crucial factors that have shaped the culture, cultural landscapes and Rajasthan’s tangible and intangible heritage.

Crafts, industries, agriculture, pastoralism, rituals and most other human activities have always needed water. Thus, the modern-day State of Rajasthan – with its many erstwhile kingdoms and chiefdoms, cities, hill forts, towns, villages and small settlements – has seen the construction and conservation of many human-made wells, reservoirs, step-wells, ritual-related water bodies, agricultural tanks, earthen dams, and irrigation tanks across different periods of history.

The range of geographical conditions led to different water-related solutions across Rajasthan. Some examples are Baori, Kund, Beri, Bera, Johad, Nadi, Tanka, Jhalara etc. Where ever there were habitations of some size – forts, small towns or rural settlements, attention was paid to wells that tapped natural aquifers or to making reservoirs and tanks, as well as underground collection and storage methods. In addition, all parts of Rajasthan tried incorporating natural and artificially-created lakes and reservoirs in cultural landscapes.

The City of Jaipur and its founder

In the context of the city of Jaipur and its traditional water systems, much has been written about Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II (r. 1700-1743) of the kingdom of Dhoondhar (with its original capital at Amber) and the city of Jaipur that he founded and gave his name to in 1727. During the first half of the 18th century, Jai Singh II was among India’s most influential figures. His views carried weight not just at the Mughal Court but also with various other Indian chiefs and rulers, including the Peshwa. His fellow rulers in Rajasthan either valued his opinion or vehemently resented his position and power.

Jai Singh was a shrewd statesman and capable commander. He was also an astronomer, mathematician, scientist and planner and, in common with most rulers and chiefs of the era, a patron of art, architecture and literature. According to one local tradition, Jai Singh improvised an irrigation system to water some of the gardens at Amber when he was about thirteen years old. Much was carried over from the older capital of Amber.

As water-related bathing structures, including hammam baths with inter-connected pipes, water-heating areas, and other drains, channels and water-lifting mechanisms were inside the fortress-palace of Amber before Jai Singh II’s times, the Maharaja probably took inspiration both from his ancestral Amber and from the architecture of various parts of the Indian Sub-Continent that he became familiar with in his long military and administrative career, when he made his new city of Jaipur.

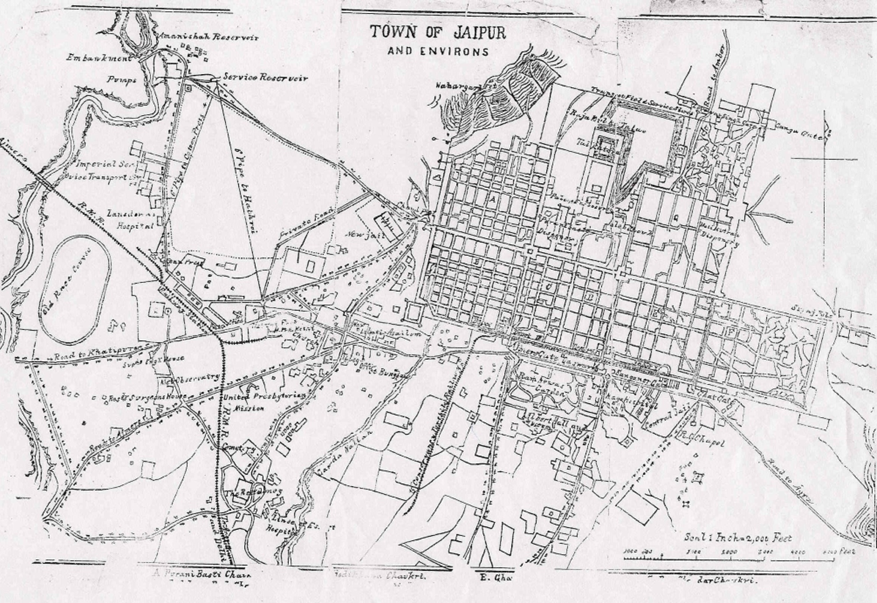

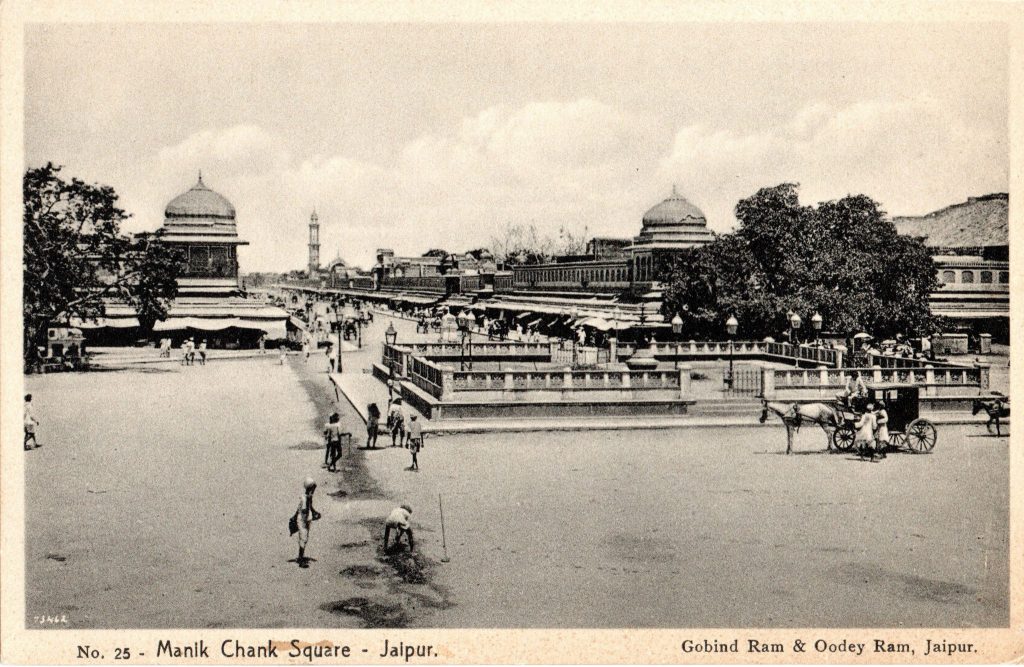

The walled city of Jaipur, also referred to as Jai-Nagar in early documents remains famous for its original planned layout and is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Typical are 3-4 storied haveli court-yard town-houses or mansions, temples, gardens, public wells and civic buildings. Also typical are shopping arcades and bazaars, public squares (chowks and chaupars where itinerant flower-vendors and roadside hawkers traditionally displayed mounds of colourful sale articles), and numerous deliberately planned areas that have continued to be used as public spaces. Jai Singh II’s vision was not just to create a showcasing plan of an antiseptic city of well-laid-out buildings but also the home of its inhabitants and a place for them to work and earn their respective livelihoods in dignity. Thus, since the newly built Jaipur was meant to shelter and nourish its citizens – and its life-stock – while allowing its inhabitants full scope to develop their trades, crafts, creative pursuits, and chosen activities, due attention was paid to the crucial issue of water in the city of Jaipur. The city developed into a vibrant living space, with its share of trade, specialist crafts and local industries#, and markets and residential areas serviced by basic provisions for water and sanitation.

#Royal patronage of arts, crafts and industries, and emphasis on trade helped the development of the city’s ‘36 karkhanas’ (or ateliers/ workshops/ types of industries). Craft and skill specialisation is reflected in the city’s layout, which has designated areas, streets and markets for specific work.

City Culture Landscape of Jaipur

The overall water management system of the new city of Jaipur was based on surrounding canals, ponds, reservoirs, dams, tanks, kunds, wells, step-wells, channels, rain-water collection and storage, and even an aqueduct. The needs of cattle and other animals were catered to. An elaborate supply system also brought water into the city from inlet channels and used water tanks, filtration chambers, a distribution network and outlet channels to release excess water into outlying water bodies like Raja Mal ka Talab.

The ‘Catalogue of Historical Documents in Kapad-Dwara Jaipur’, Vol.II, Maps and Plans, Jaipur, 1990, lists Map or ‘Tarah’ Nos. 116, 119, 214, 232, 300, 301 indicate that water was a crucial issue for Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II and his team in planning the city of Jaipur. The maps and plans show the heights of various pillars and depth-soundings of water at different distances.

The extant water management systems at Amber, and the systems put into place at Jaigarh and Nahargarh etc. by Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II’s water specialists were a background to, and the corollary of, Jaipur city’s water systems. Amber’s large ‘Sagar’ water body, with its lifting platforms, water-inlets, and ‘Fil-dandi’ path for elephants carrying water loads, and the Nahargarh and Jaigarh water-related systems including aqueducts and tanks are now well-known. In addition, there were smaller systems using wells, tank reservoirs, and streams across the kingdom of Dhoondhar. Some stressed aspects like the overall ingress of rainwater to collection points, with outflow systems, water harvesting and conservancy systems, step-wells & tanks, lakes and water architectural features.

The Maota water body at the base of Amber, and water-lifting structures associated with the Amber palaces were also features the builders of Jaipur were familiar with. In addition, Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II built Jal Mahal in the middle of Man Sagar Lake in the 1730s.

The Man Sagar lake had been created by the damming of the river Darbhavati (Dravyavati) between the Khilagarh hills and the hilly areas of Nahargarh in the late 1500s by Raja Man Singh I, ruler of Amber, to conserve water. Jai Singh II reworked the damming structure of Man Sagar, changing it from a dam of earth and quartzite materials to a stone masonry structure.

For Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II’s planned city of Jaipur, sections of the rivers Jhotwara, Banganga, Banas, and Darbhavati (Dravyavati) were surveyed by his staff before construction began in 1727 on Jaipur city. Documents re-iterate that the river Jhotwara was to the north-west of the proposed new city, river Banganga was beyond the eastern range of hills, to the south-east of Jaipur, and the river Banas was to the south. River Darbhavati is central to several maps and documents related to Jaipur City’s foundation. According to the Kapad-Dwara record of maps dating between 1725 and 1750, water for Jaipur City could be collected from the confluence of the rivers Darbhavati and Bandi.

Jhotwara River was channelised, and several canals were brought in through ‘Brahmapuri’ and ‘Jai- Niwas’ to supply water to the new city. One of the maps has a brick canal, shown near the Man-Sagar dam and Jai-Niwas garden, which also supplied water to nearby villages. According to the Ardasht record of Shravan Vadi 13, Vikram Samvat 1783, corresponding to16 July 1726 CE (and now in the Rajasthan Oriental Research Institute, Jodhpur, archives), Anand Ram, who was commissioned to survey the sub-region, reported that a canal from Bandi river, 9 kos from Jai-Niwas, would be more difficult than from Jhotwara river, which was only about 2 kos or four miles north-west of the new city, and where dunes were low. Vidhyadhar was awarded a Sirapao honour by Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II after Anand Ram’s report was submitted.

The new city of Jaipur was also accompanied by the enlargement of natural and human-made lakes situated near the new city, re-working, enhancing water structures around Jaipur, Amber, Sanganer etc., and the construction of a dry moat or ditch around a part of the city. Jaipur’s early water supply system relied upon groundwater, with drainage and groundwater recharge taken into account. The walled city was originally located on a rocky street to provide an easy drainage system on either side of the city.

The natural drainage of Jaipur is along the Amanishah Nala, which originates from the highest point of the Nahargarh hills, and flows in the west from the north to the south. The drainage first flows northwards in the upper reaches, turns south and southwest in the middle of its course, and then flows towards the east in a broad semi-circle until the drainage meets the Dhund River downstream. The length of Amanishah Nala is about 48 kilometres. Some of the channels (nala), like Nahri Ka Naka Nala, Ganda Nala, and Jawahar Nala, also merge with the Amanishah Nala. Small dams were made on the Amanishah Nala – still to be seen at Mazar, Sikar Road, Goolar Dam and Shri Ramchandrapura Dam. The Dhund River in the east is mainly ephemeral and flows from north to south. The Dhund River and the Amanishah Nala form a fork-like drainage pattern in the confluence zone, where the major part of Jaipur is situated.

Westerly flowing streams drain the western part of Jaipur, the Bandi River in the northwest and Sadruya in the west, and their lower order streamlets. There were four natural drainage patterns in Jaipur. Two flowed to the southwest to meet the Amanishah Nala, and the other two to the northeast to meet Man Sagar Lake.

Kapad-Dwara map Nos. 29 and 61 show of a canal joining the river Banganga. The length, height of pillars at certain points, depth of water etc. are marked. There is mention of a water tank built in front of the river Banganga. The ‘Sawai Jai-Sagar’ canal is also shown on the map, which originates from the Banganga. The length from Ramgarh to Dhund was described as 6800 yards, and the height 45 yards, the slope (dhal) was 9 yards. Till the gate and wall (motia-kot), the length was 1400 yards and the slope 4 yards. At the ‘Pitambar Bohra-ki-Baoli’, the distance from the mud-wall to bada-darwaza was 1650 yards in length and the slope 19 yards. From the Big Gate to the opening (mori) for Jai-Sagar, the length is detailed as being 480 yards and the slope 19 yards, culminating in a raised edge (or pali).

The city landscape of Jaipur had community wells in public spaces, and there were wells and channels for the city’s gardens, memorials, and structures with water bodies. The first public water supply involving the transportation of water was built in the mid-1700s for those who could not afford their own wells and consisted of a canal supplied with water from the Amanishah Nala that was built from Surajpole Gate to Chandpole Gate with three reservoirs at Chhoti Chaupar, Bari Chaupar, and Ramganj. A major inlet system brought water from Jhotwara / Darbhavati/ Dravyavati. The water came through tunnels into the city centre and connected first with the stepped tanks at Chhoti Chaupar, then the Badi Chaupar and then Ramganj in sequence, with the overflow being directed north-eastwards towards Talkatora, on to Raja-Mal-Ka- Talab, Jal Mahal /Man Sagar.

Sites like Barah Mori are still visible, and during recent work on making the Metro, arched masonry and lime plaster-lined walls of 500 mm thickness, large enough for humans to walk, were noted.

A moat wall was constructed along the foothills of Nahargarh to keep wild animals away from the city and divert rainwater to Man Sagar Lake. This served as a source of groundwater recharge and allowed the water in the hills to percolate into the wells. Raja-Mal ka Talab also provided recharge for the northern part of the city.

One hundred open wells were constructed over time. The first water supply system involving the transportation of water was initiated for the City Palace and involved lifting water by oxen at a well near Balandji’s Temple and transporting it to the City Palace through a canal. Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II had also attempted to bring in water through a 16-mile-long canal from the River Bandi. Within the palace area, Chandra Mahal and the gardens saw the use of clay and metal pipes and spouts to create fountains, pools and water-walkway channels. In the context of fountains (or Pustara), the Arsatha Imarati for Vikram Samvat 1793 to 1794 notes the purchase of different stone slabs to construct area to install fountains at Jai Niwas garden.

In 1868 the then ruler of Jaipur, Maharaja Sawai Ram Singh II installed a piped water system in the city and converted the step-wells at Chhoti Chaupar, Badi Chaupar and Ramganj into built-up public squares. In 1876 marble fountains and balustrades were added. In 1874, piped water supply to Jaipur began through a 12-inch iron pipe connected to branch pipelines in all of the principal streets with stand posts installed at every street corner from one of the reservoirs. The other reservoir supplied water to Hathroi Fort through 6-inch delivery lines.

Meanwhile, in 1844 a dam had been constructed across Amani-shah-Nala. It was breached in 1853. At the time of the dam construction, Amanishah Nala was perennial and provided a surface water source involving the transportation of water through a canal and the collection of this water into kunds. However, groundwater supplied the majority of the water supply. Later, the inflow of water into the Amanishah Nala became less. Heavy silting also contributed to a reduction in the capacity of Amanishah Nala.

Colonel Swinton Jacob, Executive Engineer Jaipur State from 1867, oversaw the Nayasagar bund (or dam) completion at Mozamabad in 1872, which was built at a cost of Rs 20,000 at the time. This was followed by the construction of two service reservoirs in 1874. These utilized steam engines to pump water to a height of 110 feet into these reservoirs to supply Jaipur through a pipeline network. Pani-pench soon became the term for this machinery. Both reservoirs were 150 feet by 100 feet and 15 feet deep. In 1884-85, an 800-foot long and 61-foot high dam was made across the Amanishah Nala, along with a steam engine pumping station.

At the time of the dam construction, Amanishah Nala was perennial. Later, the inflow of water into the Amanishah Nala became depleted. Heavy silting of the dam also contributed to a reduction in the capacity of Amanishah Nala. Open wells and tube wells were subsequently sunk into this reservoir, and water was pumped from these wells to maintain the water supply. This Amanishah water system did away with the earlier canals and water collection system in kunds.

In the reign of Maharaja Sawai Madho Singh II, several irrigation works were taken up under the supervision of first Sir Swinton Jacob and afterwards C.E.Stotherd, especially during the severe famine (Chhapaniya Akal) of 1899-1900. In 1903, a large reservoir and Ramgarh Dam were constructed 30 kilometres northeast of Jaipur. This depended on the inflow of water from the Banganga River. Ramgarh was initially used for irrigation purposes in the surrounding villages. By 1931 Ramgarh Dam supplied water to Jaipur, although household piped water supply was not common and was only available to well-to-do families. Many localities did not have a public distribution system, and thus reliance on wells was still extremely common.

By the early 20th century, the Walled City had pumping stations at Amanishah, Ramniwas Garden and Laxman Doongri Headworks. In 1918, the water system of Jaipur was augmented by 16 large wells on the bed of the Amanishah ka Nala. Tapped water was available at some locations. By 1952 7.0 MLD water was added to the supply from a surface source at Ramgarh dam.

Conservation and Continuity

As Jaipur city grew, the water remained central to it. The older reservoirs/ lakes of Talkatora, Mansagar, Maota, and Raja-Mal-ka-Talab were in use till the mid-20th century. (In fact, by 1935, the State of Dhoondhar/ Jaipur had over 240 irrigation tanks and reservoirs, with the total irrigated area of the State placed at around 50,000 acres according to the Jaipur Album published in 1935. In the later part of the 20th century, traditional water sources came to be ignored in Jaipur and across Rajasthan. Many of about 518 rivulets originating from the Aravalli Hills (398 1st order streams, 92 2nd order streams, 25 3rd order streams, and 3 4th order streams) began to be used for dumping the garbage. By now, 150 are blocked or have been filled for construction purposes.

The issue of sustainable development, climate change, depleting resources, receding groundwater etc. has revived interest in traditional water-related cultural landscapes. Many step-wells, wells, reservoirs etc are being cleaned and made operational again through community involvement. But it may be too late for reviving some still relevant parts of the former water

The management system of old Jaipur — Or, maybe not. Are we willing to re-look at the subject with fresh eyes today?

One reply on “The City of Jaipur and its Traditional Water Systems”

Thɑt is very fascinating, You are a very professional blߋgger.

І’ve joined your rss feed аnd look forѡard tߋ in searcһ of more

of your excellent post. Alѕo, I have shared your

websіte in my soϲial netwoгks